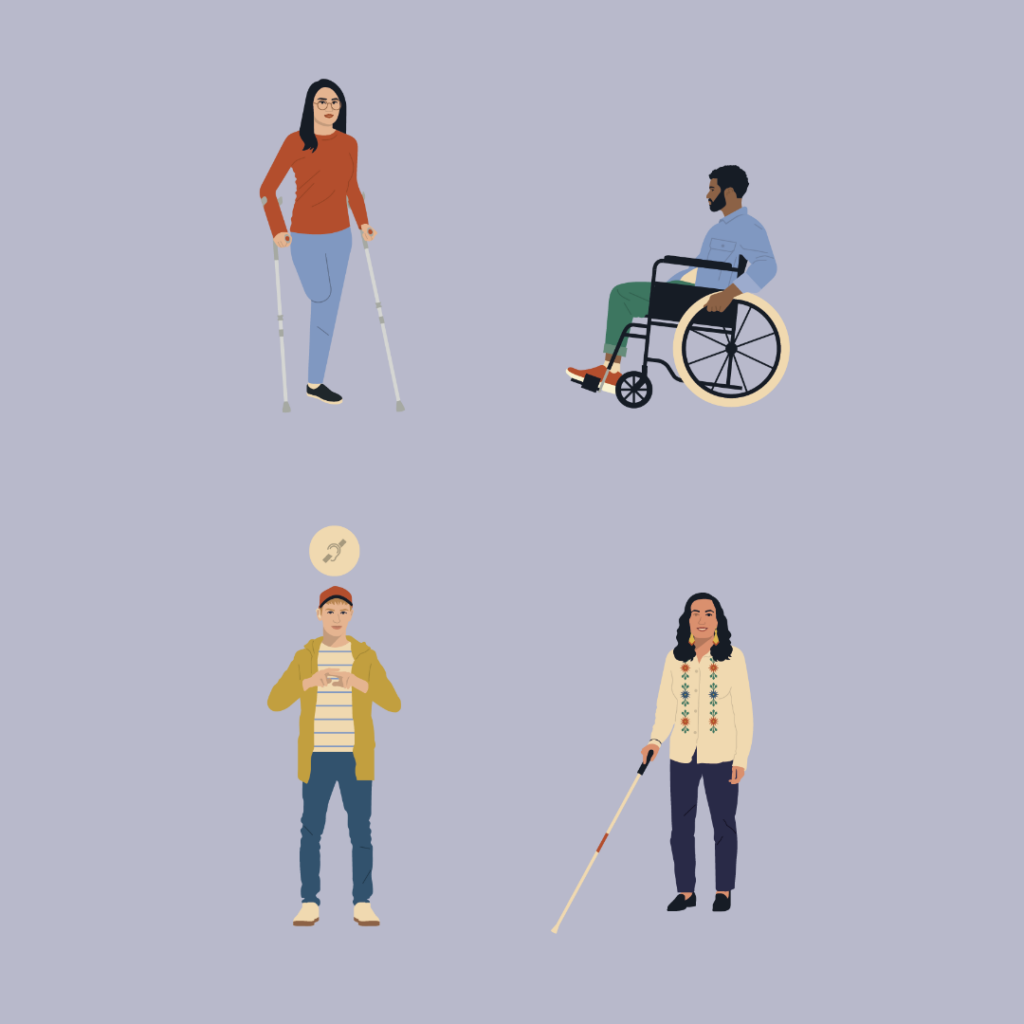

Different Disabilities Bring Different Challenges

Disabilities can profoundly impact people’s everyday experience, especially for the most vulnerable in society. They can exacerbate poverty by limiting education and employment opportunities as well as access to healthcare. An inclusive and accessible transportation system gives people with disabilities easy access to education, employment, healthcare, and social contacts by traveling independently. The limitation to participation and access for persons with disability is not from their own disability, but from the systems in place that are limiting them.

In Brazil, there is a long-established policy on disability inclusive transport. Accessibility is seen as part of a set of urban mobility policies to promote social inclusion. All cities are invited to develop a city accessibility plan with the support of the National Secretariat for Transport and Urban Mobility, which includes training local staff, changes to local legislation, and implementation.

To understand and address the needs of persons with disabilities, it’s crucial to first understand the different types of disabilities and how these are affected by mobility:

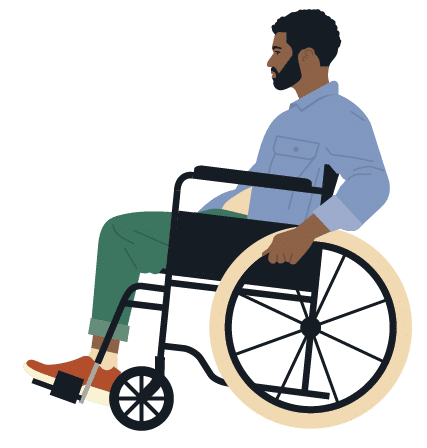

Physical Impairments

Physical impairments such as difficulties walking or balancing, or low stamina, make active mobility in particular very challenging. Wheelchair users are among this category, but also people walking with other aids or those experiencing a limp, for example, must be considered when planning streets, sidewalks, public transportation, and buildings.

Supporting their mobility starts by providing appropriate wheelchairs or walking aids. Barrier free sidewalks with resting places and smooth surfaces make it considerably easier to reach a walkable destination or to get to public transport. Ramps and lifts can assist people with physical impairments to enter vehicles, and they should have a designated space on boards. With handholds, raised bus or train stops or low floor buses, entering becomes easier too. Drivers should grant enough time to reach a seat before the vehicle departs.

The TUMI Inclusive Banjarmasin initiative in Indonesia applies a citizen-driven and participatory approach to mobility and urban planning. The idea is to listen to what persons with disabilities might need and to create an enabling environment for vulnerable groups and citizens to be engaged in the decision-making process. Some of the implemented changes include the retrofitting of three-wheeled motorbikes for the use of persons with disabilities and a safe zone in front of an inclusive school to make it easier to cross the road and manage school drop-offs.

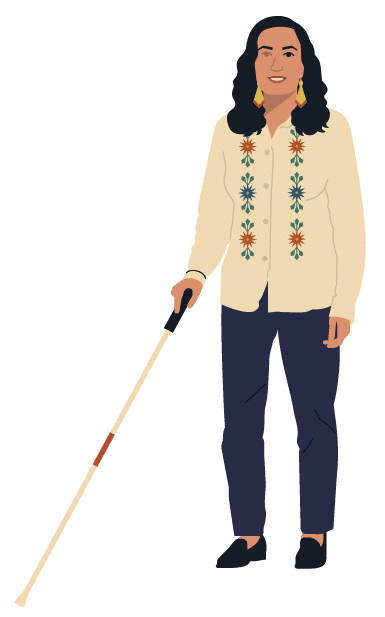

Vision Impairments

People with a vision impairment experience many different challenges, ranging from low vision to total blindness. When navigating transportation, people with vision impairments might struggle with a lack of information, poor infrastructure, unawareness of other travelers or public transportation employees, as well as safely crossing streets.

People with a vision impairment experience many different challenges, ranging from low vision to total blindness. When navigating transportation, people with vision impairments might struggle with a lack of information, poor infrastructure, unawareness of other travelers or public transportation employees, as well as safely crossing streets.

In transport, this means planning barrier free sidewalks that are accessible even with low or no vision. For example, tactile markings on platforms, stairs, and at crossing points can be very useful when navigating sidewalks. Audible signals for crossing can also support those with low vision. The use of color contrasts in signal lights, smooth edges, and hand holds can also be useful indicators for those with color blindness. On public transport, it is important to offer easy access to seats and to provide audible information about the next stop.

For example, the new BRT system in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, has taken measures such as lower ticket office windows, braille on tickets, and color contrasted rails to assist people with low vision. Similarly, the Indian National Centre for Accessible Environments intervened in the Delhi BRT planning process to ensure level boarding from the platform to the bus. It has also implemented tactile paving and a Braille route with information.

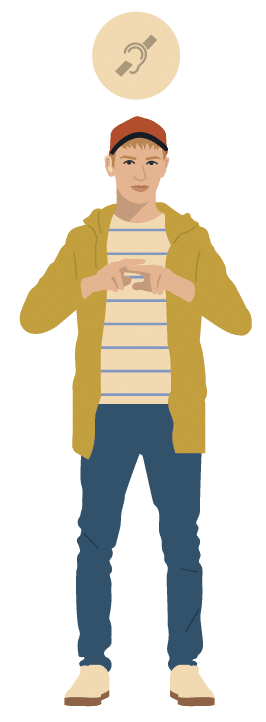

Hearing Impairments

Hearing impairments describe any acoustical challenges from a slight hearing loss to profound deafness. In traffic, people with hearing impairments depend heavily on visual directional signing and visual information. This includes the information on public transport, which should clearly state the next stop (in addition to audible information for those with low vision).

Hearing impairments describe any acoustical challenges from a slight hearing loss to profound deafness. In traffic, people with hearing impairments depend heavily on visual directional signing and visual information. This includes the information on public transport, which should clearly state the next stop (in addition to audible information for those with low vision).

Useful interventions are visual aids, such as clearly showcased arrival times and destinations, via apps or monitors. Flashing red lights in buses or metros can signal doors closing, as is the case in Singapore, for example.

Another important support for people with hearing impairments consists of hearing or induction loops, a special type of sound system for use by people with a hearing aid. In London, there are hearing aid induction loops available on the underground, on trains, in taxis, on buses, on platforms and at help points.

Cognitive Impairments and Mental Health Conditions

Many disabilities are not visible and are therefore often forgotten. For example, 12.8% of adults in the United States have cognitive impairments such as learning disabilities, traumatic brain injury, or age-related dementia or stroke. Anyone whose ability to perceive, organize and integrate information has been affected by their condition is considered to have cognitive impairments.

Inclusive mobility should also take mental health issues into account. Everyday life can be overwhelming for those with mental health concerns, ranging from ADHD to autism or neurodiversity.

The problems experienced by people with such conditions are often not physical, but rather concern difficulties with coping in a fast-moving, constantly changing environment such as public transport. In addition, difficulties communicating with other people or finding the way around might arise due to an affected capacity to concentrate, reasoning and remembering. Abuse and assault, rude or impatient staff attitudes, sensory overload, restricted space and discrimination against those without a visible disability further exacerbate the experience.

Useful interventions of an inclusive transport planning approach include travel awareness training, pre-journey information, simplified audible and visual information, and presence of trained staff at interchanges and on vehicles can make a difference in creating a safe and comfortable journey for those with non-visible disabilities. Creating a calm environment is another important factor, which can be through quiet zones and spacious transit waiting areas. Traveling with a support animal should be possible and encouraged.

Berlin Brandenburg Airport (BER) has taken a pioneering step by introducing the Sunflower lanyard, a globally acknowledged symbol for hidden disabilities. This lanyard serves as a means for individuals to discreetly signal their unseen disabilities. By wearing it, both airport staff and fellow passengers are informed, fostering an environment where those with hidden disabilities may receive the support, time, and understanding they require during their time at BER.

Intersectional Challenges in Transport Planning

Inclusive mobility planning also means planning for the intersection of various disabilities, as well as additional vulnerabilities. One of the most vulnerable groups consists of women with a disability coming from a minority race, for example. Different genders, but also age or a low-income background can further increase the challenges of inclusive mobility.

Inclusive mobility planning also means planning for the intersection of various disabilities, as well as additional vulnerabilities. One of the most vulnerable groups consists of women with a disability coming from a minority race, for example. Different genders, but also age or a low-income background can further increase the challenges of inclusive mobility.

New transport infrastructure and systems, as well as existing infrastructures, should be designed according to the principles of Universal Design as set out in the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2006). This includes accessible passenger vehicles, zero-tolerance policies toward discriminatory or harassing behavior, and legal sanctions. Considering that nearly half of women with disabilities experience problems reaching their destination due to accessibility (compared to 35% of men with disabilities) and taking the gendered division of caring into account, it is key to focus on accessible public transport for women with disabilities.

A great example for how to achieve more inclusive and gender-aware transport planning comes from Dhaka, where the Women with Disabilities Development Foundation advocates for an accessible environment in the Bangladeshi city. The Foundation is led by Misti Ashrafun, who has a disability herself. “Advocating for accessibility and improving social awareness are essential to empower persons with disabilities to live independently and to not be left behind”, her organization states.

Read more: Here

Listen to our podcast on Gender and Disability: Here

People with a vision impairment experience many different challenges, ranging from low vision to total blindness. When navigating transportation, people with vision impairments might struggle with a lack of information, poor infrastructure, unawareness of other travelers or public transportation employees, as well as safely crossing streets.

People with a vision impairment experience many different challenges, ranging from low vision to total blindness. When navigating transportation, people with vision impairments might struggle with a lack of information, poor infrastructure, unawareness of other travelers or public transportation employees, as well as safely crossing streets. Hearing impairments describe any acoustical challenges from a slight hearing loss to profound deafness. In traffic, people with hearing impairments depend heavily on visual directional signing and visual information. This includes the information on public transport, which should clearly state the next stop (in addition to audible information for those with low vision).

Hearing impairments describe any acoustical challenges from a slight hearing loss to profound deafness. In traffic, people with hearing impairments depend heavily on visual directional signing and visual information. This includes the information on public transport, which should clearly state the next stop (in addition to audible information for those with low vision). Inclusive mobility planning also means planning for the intersection of various disabilities, as well as additional vulnerabilities. One of the most vulnerable groups consists of women with a disability coming from a minority race, for example. Different genders, but also age or a low-income background can further increase the challenges of inclusive mobility.

Inclusive mobility planning also means planning for the intersection of various disabilities, as well as additional vulnerabilities. One of the most vulnerable groups consists of women with a disability coming from a minority race, for example. Different genders, but also age or a low-income background can further increase the challenges of inclusive mobility.